Dr. Kasten is a practicing Theophostic counselor in Michigan in addition to his course creation and teaching work with MJR Yeshiva. He also holds an M.A. in Chaplaincy.

Dr. Kasten is a practicing Theophostic counselor in Michigan in addition to his course creation and teaching work with MJR Yeshiva. He also holds an M.A. in Chaplaincy.

The Tetragrammaton Hidden in Esther

You’ve no doubt been told at some point that the name of G-d is absent from the book of Esther… but is it really? It might be rather telling that the name “Esther” (אסתר) means “I will hide” in Hebrew.

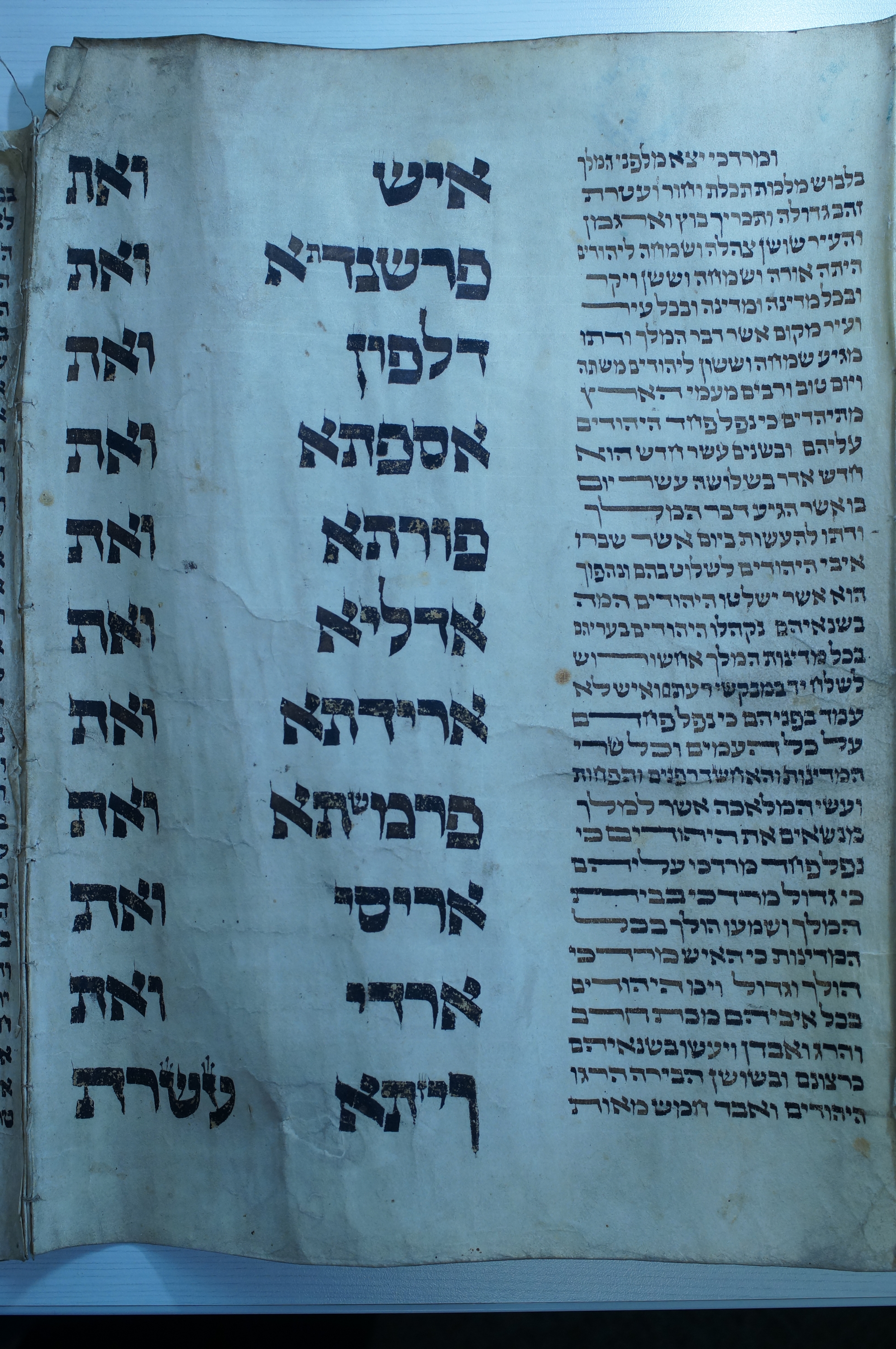

During Purim, when the Megillat Esther is read from the bimah, one might notice in the scroll a series of four letters are either enlarged or specially ornamented at four points in the scroll. These occur (when they are present, usually in Chasidic copies of the text) at:

- 1:20 הִ֑יא וְכָל־הַנָּשִׁ֗ים יִתְּנ֤וּ (it all the wives shall give)

- 5:4 יָבֹ֨וא הַמֶּ֤לֶךְ וְהָמָן֙ הַיֹּ֔ום (let the king and Haman come today)

- 5:13 זֶ֕ה אֵינֶ֥נּוּ שֹׁוֶ֖ה לִ֑י (this avails me nothing)

- 7:7 כִּֽי־כָלְתָ֥ה אֵלָ֛יו הָרָעָ֖ה (that there was evil determined against him)

In the first two instances, look at the initial letters of the four words (left-to-right in 1:20 and right-to-left in 5:4). What do they spell? In the last two instances, look at the final letters of the four words (left-to-right in 5:13 and right-to-left at 7:7). They spell the same name. These are understood by many of the Sages to be crypto-occurrences of the Covenant Name of HaShem, i.e. the Tetragrammaton, hidden within the text. Interestingly, the two instances where the name is spelled left-to-right occur in verses spoken by gentiles (Memuchan and Haman), and the two where the name is spelled right-to-left are found in the words of Jewish speakers (Esther and the author, presumably Mordecai).

Some have claimed that the absence of this name accounts for this book’s absence from the Dead Sea Scrolls cache… but a manuscript from that cache designated 10QEsth has recently been identified as a fragment from Esther, finally dispelling the six-decade-old myth. A thetorah.com article by Dr. Rabbi Asher Tov-Lev breaks the news on this discovery: https://thetorah.com/newly-deciphered-qumran-scroll-revealed-to-be-megillat-esther/ (27 Feb 2018).

Some have claimed that the absence of this name accounts for this book’s absence from the Dead Sea Scrolls cache… but a manuscript from that cache designated 10QEsth has recently been identified as a fragment from Esther, finally dispelling the six-decade-old myth. A thetorah.com article by Dr. Rabbi Asher Tov-Lev breaks the news on this discovery: https://thetorah.com/newly-deciphered-qumran-scroll-revealed-to-be-megillat-esther/ (27 Feb 2018).

Also of interest regarding the Esther Scroll is the list of Haman’s hanged sons in 9:7-9. In every known Megillat Esther manuscript, it is a specially formatted passage with three suspended letters and one enlarged letter (see below).

The suspended letters have traditionally been understood to be highlighting their numerical values, and the enlarged waw as indicating the 6th Millennium. Thus, they seem to be pointing to a particular year on the Biblical Calendar.

- ת = 400

- 300 = ש

- 7 = ז

- 6th Millennium = ו

Their sum indicates Creation Year 5707, which runs from September 1946 to September 1947. On October 1, 1946 (which falls within that Biblical Year during the feast of Sukkot), a trial took place in Nuremberg, Germany in which twelve Nazi leaders were sentenced to death by hanging. One of the twelve, Hermann Goering, committed suicide in advance of the scheduled hanging, and another, Martin Bormann, was tried in absentia and was not in custody for the hanging, leaving ten to be put to death on the assigned date, i.e. October 16th of that same year. [1] One of the ten, Julius Streicher, uttered his final words on the way to the gallows: “Purim Fest ein tausend neun hundert sex-und-vierzig” (Festival of Purim 1946), seemingly recognizing that the hanging of himself and his nine comrades was a second fulfillment of judgment against Israel’s enemies.

Two other enlarged letters occur in the text: the chet of 1:6 and the taw of 9:29. It is suggested that these letters in the Ashuri block script of Hebrew both have the appearance of a gate. The reason for their enlargement is to emphasize, the Sages explain, that the Jewish community should open wide both its front door and its back door, so that all who wish – both rich and poor – may join us [2].

Now Accepting Book Submissions

-

הוֹצָאָה לְאוֹר

MJR has just launched our own publishing house: MJR Press. We will be publishing works in the following areas of Jewish culture:

- Bible (includes Parashot & Haftorot studies, commentaries, & original midrash)

- Rabbinical Literature (introductions, commentaries, monographs, tutorials, etc.)

- Halakha

- Prayer/Liturgy

- History/Biography

- Hebrew & Cognate Languages

- Classic Reprint Series: Judaica & Hebraica

Our first Classic Reprint, Granville Sharp’s A Letter respecting Some Particularities of Hebrew Syntax (London, 1803), will be available by the end of April 2017, and Brian Tice’s Reflecting on the Rabbis: Sage Insight into First-Century Jewish Thought will be out in May 2017.

Granville Sharp was the very definition of a Renaissance Man: self-taught in Law, Hebrew, Greek, and Music – and highly accomplished in all of them. In this formerly out-of-print work, Sharp dissects all of the available grammars for any inkling of data on the function of the waw-hahipuch and proceeds to formulate the most comprehensive set of rules with regard thereto, complete with examples from Scripture. This edition includes a new biographical introduction and an annotated bibliographical survey of the grammars with which Sharp interacted. As an added bonus, Granville Sharp’s rather impressive family is presented in a family tree in the inside back cover.

We used to know a lot about First-Century Judaism… until we realized we didn’t. The First Century CE was what is known as Judaism’s “creative phase.” There were Sadducees, Pharisees, Zealots, Essenes, Therapeutae… just to name a few of the Jewish sects and movements. And, most of these had sub-sects or sub-movements of their own as well. The Pharisaic sect was certainly no exception. In this volume, Jewish Studies professor Brian Tice presents the six most prominent and influential Sages of this period, drawing from the Bible, both Talmuds, the Midrashic literature, the Targums, and other scholarly sources to set the scene of a First-Century Judaism which is likely more diverse than you realized. What were the essential beliefs? Who were the main players? Where did their worldviews differ? What were the religious politics? What was considered out of bounds? The author takes readers on a pilgrimage through the rabbinical schools of some of the greatest Jewish minds of the time period to offer some “Sage insights into First-Century Jewish thought.” <b>Recipient of the 5777 Yiddishkeit 101 College-Level Literature Award!</b> Order in June, and get free enrollment in the MJR course which corresponds to the book! https://mjrabbinate.teachable.com/p/fjt-120/

Your Jewish literature proposals or submissions can be sent to us at publishing@mjrabbinate.org.

How to address a Rabbi

The norms of civilized society require certain things with regard to addressing others in discourse. For example, it is considered improper to address an adult by his or her first name unless and until invited to do so. In Yiddish, granting this permission is called dutzening. If you have not been dutzened to use a person’s first name, you use the civil convention of calling the person by title, for example: Miss, Ms., Mrs., Madame, Mr., Master, Professor, Dr., etc. There are some titles which require address by circumlocution. These traditionally include royalty (His/Her/Your Majesty), non-royal rulers of countries (Your Excellence), judges (Your Honor),* and Rabbis (Rabbi; Rabbeinu, i.e. “Our Great One;” or l’kavod haRav, i.e. “for the honor of the Rav”).

The norms of civilized society require certain things with regard to addressing others in discourse. For example, it is considered improper to address an adult by his or her first name unless and until invited to do so. In Yiddish, granting this permission is called dutzening. If you have not been dutzened to use a person’s first name, you use the civil convention of calling the person by title, for example: Miss, Ms., Mrs., Madame, Mr., Master, Professor, Dr., etc. There are some titles which require address by circumlocution. These traditionally include royalty (His/Her/Your Majesty), non-royal rulers of countries (Your Excellence), judges (Your Honor),* and Rabbis (Rabbi; Rabbeinu, i.e. “Our Great One;” or l’kavod haRav, i.e. “for the honor of the Rav”).

The Chakhmim (Sages) give explanation on why a rabbi is to be so addressed.

Rabbi Akiva ben Yosef taught: “Et Hashem Elokecha Tira (you shall respect HaShem your G-d – D’varim 6:13); l’Rabot Talmidei Chachamim (respect Torah scholars as well)” (b. Pesachim 22b).

Rashi taught: “You shall respect your rabbi as you respect Heaven” (Commentary on b. Pesachim 22b).

The Rambam taught: “One should not greet his Rabbi, or return greetings to him, in the same way that people greet friends and return greetings to each other, but one should bow slightly in front of him and say in reverence, ‘Shalom to you… Rabbeinu.’” (Hilchot Talmud Torah 5, Halakha 5).

In a letter, direct address is acceptable, in the form: “Dear Rabbi (surname),” though “l’kavod haRav” is preferred. Use of the first name, however, is perceived as contempt… unless that particular rabbi has dutzened you. In any formal setting, e.g. worship, though — l’kavod haRav should be used regardless of any dutzening that might define address in private conversation.

It used to be that the title of Rabbi was reserved for use in Eretz-Israel, while the diaspora Torah-teachers were given the title Rav; but today those two terms are interchangeable in most contexts. Some yeshivot will call those who have received shemikha by rabbi and those who are in the process leading up to shemikha by the title rav, treating it as lesser. In Yiddish, especially among the Ashkenaz, the title of rebbe is often preferred (as used in “Fiddler on the Roof”), and in Sephardic communities, both rabbi and chakham are used, with the latter being a bit higher in rank (on par with rabban in ancient times).

If in doubt: address everyone by title unless or until directed otherwise.

*Note that “Your” is the respectful form; “thy, thine” is the familiar, and thus is deprecated as insulting.

MJR Yeshiva is Live!

MJR has launched eleven courses for the summer with more in development! Enroll now in any of the following at just $140/12-week course:

- ARAM-101 Biblical (OT) Aramaic

- BIB-101 Tanakh (OT) Survey

- BIB-110 Bible Exegesis – Torah

- BIB-201 Bible Exegesis – Early Prophets

- BIB-220 Bible Exegesis – Wisdom & Poetry

- BIB-420 Bible Exegesis – Romans

- HEB-101 Biblical Hebrew I

- HEB-310 Advanced Hebrew Exegesis – Torah

- LAN-101 Sociolinguistics

- LAN-230 Ancient Ugaritic

- RAB-490 Semikha Examination

Also, for those new to Messianic Judaism, we are offering for free:

And, coming very soon…

- BIB-105 Messianic Apologetics

- BIB-210 Bible Exegesis – Latter Prophets

- BIB-401 Paul in Proper Perspective

- BIB-410 Bible Exegesis – Hebrews

- BIB-420 Bible Exegesis – Romans

- GRK-101 Koine Greek I

- GRK-201 Koine Greek II

- GRK-301 Greek Semantic Analysis I

- GRK-401 Greek Semantic Analysis II

- HEB-201 Biblical Hebrew II

- HEB-301 Intermediate Hebrew (coming in September 2016)

- IMJ-091 Intro to Messianic Judaism

- RAB-230 Counseling Strategies for the Spiritual Battlefront

What is semikha l’rabbanut?

Semikha l’rabbanut, or סמיכה לרבנות, is the process through which a person becomes ordained as a rabbi.

Semikha l’rabbanut, or סמיכה לרבנות, is the process through which a person becomes ordained as a rabbi.

The root of semikha (סמך — (סמיכה — means “to be authorized,” thus סמיכה לרבנות means “to be authorized for rabbinic office,” or more simply “rabbinic ordination.”

The practice finds Scriptural imprimatur in Torah, i.e. B’midbar 27:15-23 and D’varim 34:9. These passages reflect the סמיכה of Yehoshua bar Nun by Moshe via the laying on of hands. Note that “laying on” is also within the semantic range of “סמיכה.” This practice is conveyed through the Sanhedrin in Second Temple Times, and some suggest continued beyond the destruction of the Second Temple.

The process involves an examination of beliefs in order to qualify only those who prove not to be heretical in their beliefs and teachings. The belief criteria for ordination are listed and expounded on a separate page on this site. Candidates must be able to articulate their beliefs and defend them, as well as discern heresy or false teachings/teachers and defend against such.

The process concludes with the proclamation (if the candidate successfully passes), carried over from the ancient formula: “Yoreh? Yoreh! Yaddin? Yaddin!” (“May he decide? He may decide! May he judge? He may judge!”).1 Today, some rabbinical seminaries and yeshivot grant סמיכה לרבנות using this same ancient pronouncement.

Once having received this decree, the candidate (initiate) is certified for the issuing of halakhic judgments (yoreh), ruling in monetary and property disputes (yaddin), and presiding over the training of congregational leaders (zaqenim, morehim, and shammashim). Some congregations require סמיכה לרבנות for those who lead the congregation as well. Prior to סמיכה לרבנות, the candidate is referred to as “Rav;” afterward, he may use the title of “Rabbi.”

Those candidates who successfully complete the סמיכה לרבנות we offer will receive a plastic ID card (necessary to gain entry into jails, prisons, and some mental institutions for ministerial service) which includes the ordination date, the ordaining authority, and a personal ID number.

References

- s.v. “Semikhah;” In Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok & DanielCohn-Sherbok, A Popular Dictionary of Judaism (New York, Ny.: Routledge, 2013), 131. ↩